By Michael Q. Bullerdick

Although it’s true death row guards once routinely wagered on what a condemned man might select for his last meal, the morbid game was abandoned long ago, less out of empathy than boredom. That’s because, for the better part of a half-century or so, the penultimate menu has been fairly predictable: fried chicken, a cheeseburger or steak cooked medium rare and served with some kind of potato (almost always French fries), followed by pie á la mode (apple or pecan) or a bowl of ice cream. The real gamble, it seems, is not what an execution-bound inmate will eat—but if they’ll eat. And that decision, Cornell University researcher Kevin Kniffin recently revealed, can be a reliable “tell” of whether an inmate knows or has convinced himself that he’s innocent.

The idea that our conscious or subconscious mind could impact such matter-of-fact decisions is not as peculiar as it seems at first glance. Researchers long ago discovered a link between emotional states and the act of consumption, including which personality types drink and eat more when depressed versus those who do the opposite while in the same emotional state. What’s more, researchers have also shown how foods can be imbued with significance depending on social context and deeply ingrained belief systems. Holiday meals exemplify the point perfectly. A turkey dinner is just that—but serve it to family and friends on Thanksgiving and it becomes something special. Similarly, a pint of chocolate ice cream can seem deeply romantic if you have someone to share it with on Valentine’s Day, but it can become a pitiful means to drown your sorrows if you’re depressed about being alone. Pairing a cracker with a sip of wine could hardly be described as anything more than a meager snack, but consuming the same during Sunday church service represents the ritualistic means for entering into communion with God to billions of devout Christians worldwide.

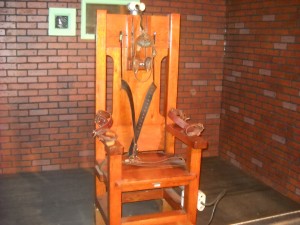

To those on death row, a last meal represents far more than a last chance to eat. Viewed from a psychological perspective, it’s both a powerful final sensory experience and a rare opportunity to assert one’s will after being experiencing a severely restrictive form of incarceration. Given all that, a last meal should be extremely appealing to both the innocent and the guilty. But that’s not always the case. In fact, a significant number of inmates choose to assert their will by rejecting their last best perk. Why—and what’s to be gained? Could such refusals be rooted in the level of remorse we like to think guilty people experience, especially during their final hours? Or is it rooted in the despair and abject fear that the innocent must suffer while execution looms?

For his part, Kniffen hypothesized that those who knew themselves to be innocent— or had truly convinced themselves they were—would request lighter meals or reject them outright due to emotional turmoil arising from a profound sense of injustice. In such cases, he suspected they might have trouble bringing themselves to eat due to feelings of frustration, anger and terror coalescing in “a desire to withhold consent for the proceedings,” Kniffen wrote in describing his findings in the journal Laws. Contrastingly, Kniffen theorized that inmates who had accepted or confessed their guilt would likely feel some measure of relief and be able to indulge in the same way that Marion Pruett managed it. Preutt, a spree killer executed in Arkansas in 1999, confessed his murderous misdeeds and then ordered a high-calorie last meal, explaining that he could enjoy it because he had “made his peace.”

To test his hypothesis, Kniffen reviewed the records of 247 executions that occurred in the United States between 2002 and 2006 and correlated last meals (acceptance or rejection) with the last words of inmates who either “(1) denied guilt; (2) admitted guilt or apologized; or (3) made a minimalist statement in which they neither denied nor admitted guilt or declined to speak.” In line with his theory, Kniffin’s analysis revealed that those who had denied guilt were 2.7 times more likely to decline a last meal than those who admitted guilt. A secondary finding revealed that those who admitted guilt were more likely to request brand name foods and last meals that were 34% higher in calories—proving, at least, that confession may be as good for the appetite as it is for the soul.

An additional implication of Kniffen’s findings may further complicate the much-debated subject of legal competency—an individual’s ability to understand the consequences of his actions and accept his penalty. In fact, an anecdote involving executed killer Ricky Rey Rector’s last meal has already factored into the issue of how competency should be assessed and managed when it comes to capital punishment. On execution day in Arkansas, Rector had reportedly asked guards that were taking him to the lethal injection chamber to save his slice of pecan pie for when he returned. Rector had been sentenced to execution over the shooting death of a police officer. His attorneys argued, however, that his subsequent botched suicide attempt, which had resulted in an accidental lobotomy, made the death penalty highly unwarranted since Rector’s mental faculties were insufficient to grasp his circumstances or testify and because the bullet to his brain had rendered him docile and incapable of future violence. His team lost the argument and the case, followed by several appeals, before Rector was put to death on January 24, 1992. Given his unnerving request, however, they may have had a valid point.

Of course it would be folly to require that judges and state governors consider granting last-minute stays of execution on the basis of an inmate’s decision to decline a last meal. Kniffin himself rejects such a notion as “an over merited implication of his findings that could routinely “encourage the denial of a last meal” by inmates seeking to game or mock the justice system. Texas death row inmate Lawrence Russell Brewer did just that, ordering an extravagant meal and then refusing to touch a bite of it before his 2011 execution for the racially motivated dragging death of James Byrd, Jr.

To the extent that Kniffen’s research can be used to determine absolute guilt or innocence, he’s quick to caution it “can only provide a dimension of ad hoc analysis.” He doubles down on the point in his conclusion, writing, “It is possible these findings could influence future considerations involving executions…. [But the data] should be most useful for understanding and assessing the innocence and perceived innocence of people who have been executed in the past.”

That may be so but there’s no doubt the findings will add to the complications and contentiousness of future death row appeals, especially cases such as Ricky Rey Rector’s, that seem to challenge the legitimacy of an execution.

Pingback: Derrick

Pingback: Gilbert

I discovered your page and noticed you could have a lot more traffic. I have found that the key to running a website is making sure the visitors you are getting are interested in your subject matter. There is a company that you can get visitors from and they let you try their service for free. I managed to get over 300 targeted visitors to day to my website. Visit them today: http://go.pigmeu.net/6fX

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful post. Many

thanks for providing these details.

Blog looks nice. I’m still trying to make a blog but it won’t be as professional as yours /: Keep on blogging 🙂 pirater un compte facebook

Marvelous, what a webpage it is! This blog gives useful information to us, keep it up.

Hey very interesting blog!

Than you

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.

Your website offered us with valuable info

to work on. You have done an impressive job and our entire community will

be thankful to you.

I visit everyday some websites and blogs to read posts, except this webpage offers quality based

content.

It’s nearly impossible to find well-informed people in this particular

subject, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this website.

I really hope to view the same high-grade blog posts by you later on as well.

In fact, your creative writing abilities has motivated me to get my own, personal blog now

😉

I really like and appreciate your blog article. Really Great.

Sweet blog! I found it while surfing around on Yahoo News.

Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed in Yahoo News?

I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there!

Many thanks

This is my first time pay a visit at here and i am actually happy to read everthing at alone place.

We stumbled over here by a different page and thought I should check things out.

I like what I see so now i am following you.

Look forward to finding out about your web page for

a second time.

I could not resist commenting. Well written!

Wonderful items from you, man. I have take into accout your stuff

prior to and you’re simply too fantastic. I really like what you have obtained here,

really like what you’re saying and the way by which you

assert it. You are making it entertaining and you still take care

of to keep it smart. I cant wait to read much more from you.

This is actually a tremendous web site.

This is my first time visit at here and i am really impressed to

read all at single place.

Enjoyed reading through this, very good stuff, thanks.